At this years annual conference the Public & Commercial Services Union (PCS) launched a booklet that provides information on the threats and consequences of privatising public services. The document builds on a series of forums that took place during 2009/10.

At this years annual conference the Public & Commercial Services Union (PCS) launched a booklet that provides information on the threats and consequences of privatising public services. The document builds on a series of forums that took place during 2009/10.

These forums examined and exposed many past failures of the privatisation of public services and made a case for well funded public services delivered by the public sector. Although taking this stance the booklet is primarily a discussion document designed to be thought provoking and challenging, seeking to provide further debate on the topics covered.

PCS National Vice President John McInally speaking in his keynote speech:

Those who advocate privatisation forget history: We must not. The public services were won, in some cases, by generations of trade union and working class struggle in an effort to establish the basis of civilised existence in a society run for profit not people. The private sector either could not or would not, or simply failed to provide effective and efficient public sector provision. The broad mass of people in society, particularly working people, need the public services – generally speaking, the rich don’t.

The establishment of public services represent reforms that the profiteers despise and which they want to destroy or exploit for profit, yet the record of the private sector in delivering privatised services is lamentable. The presentations by our Research Officers strip bare the political agendas and the performance failures of privatisation in health, transport, justice and other sectors.

The profiteers and the government have created what they shamelessly described as a “public services industry”, currently estimated at £79 bn per annum. Big business have used the so-called Third Sector, i.e., the charitable and voluntary sectors as a Trojan horse, their words not mine, in order to gain access to government contracts.

John then goes on to say:

The reconfiguration or “reform”, as it is misnamed, of public service is about preparing for eventual privatisation. Face-to-face contact is discouraged: it is old-fashioned apparently. consultants have sold to ministers ans senior civil servants the idea that call centres, telephony and electronic communication can deliver it all.

Of course there is a place for these new methods and technologies, but they can never be a replacement or substitute for the public service ethos of well-trained committed staff dealing with and resolving the complex problems of real people. Poorly paid and trained staff working from a “one-size-fits-all” script simply cannot deliver an effective service to those who require them.

The proliferation of call centres in recent years has been based on an attempt to establish regimented, factory-style conditions, a remorseless target driven environment, preferably with a transient workforce that is young, inexperienced, non-unionised and compliant. The strategic aim is to establish as few discrete units as possible to “deliver” the service at the lowest possible cost in order to hand over for privatisation so that profits can be maximised.

The booklet traces the history and origins of privatisation right back to the rise of industrial power:

The roots of privatisations also go back to the early 20th century and ruling class fears that universal suffrage in western societies would mean the erosion of their power and wealth. As trade unions and mass labour parties looked like achieving the power to place control of natural resources and the “commanding heights” of the economy under democratic control, the business elite mobilised on several fronts to protect themselves.

They responded in two ways – organisationally and ideologically. Organisationally, employers’ associations such as Aims of Industry combined to counter the rise of democratic socialism. The goal of Aims of Industry was to “defend private interest against democratic reform with the explicit aim of countering the emerging pressure for nationalisation of industry”. these days, powerful and influential bodies such as the Bilderburg Group and the Trilateral Commission bring together business and political leaders to develop long-term strategic plans to protect corporate power, destroy trade union influence, liberalise markets, privatise public services and to remove social protections created by national governments and labour movements.

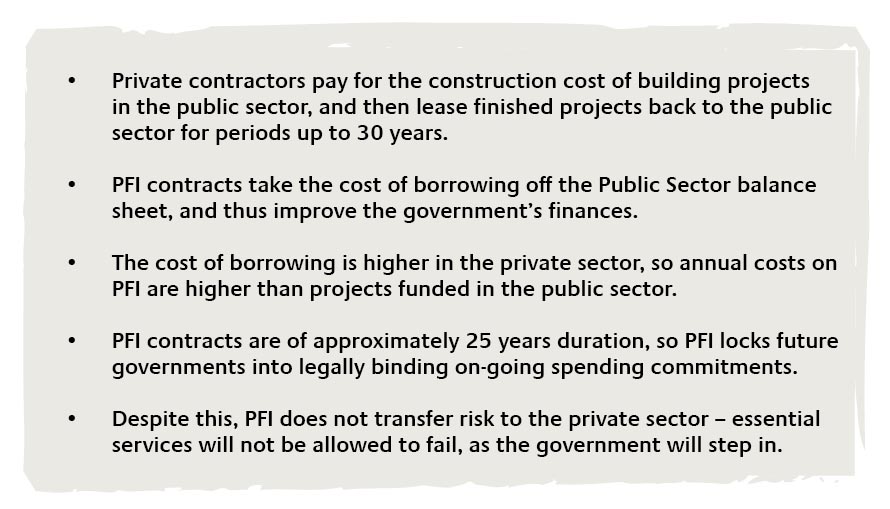

After addressing the history of privatisation the booklet moves on to the application of the privatisation model in the UK and the use of Private Finance Initiative (PFI).

Why PFI? After the big State Owned Enterprises were sold off by the Tories in the 1980s and 90s, New Labour needed a different method to transfer public services and utilities to the private sector, even thought there was little evidence of better private sector performance. In thrall to a “private-good, public-bad” mythology, and (more importantly) eager to direct lucrative public sector work to their friends in business and the city, Labour decided to enlarge the fledging PFI scheme.

PFI has many short-term advantages to government, but many disadvantages to wider society:

The public deficit is now £165 billion and the major political parties and most commentators consider this requires huge spending cuts:

Yet this deficit does not include over £200 billion of PFI debt repayment. Thus even where the government(s) speak of “ring fenced” budgets in health and education, this will still mean savage cuts in those areas as massive and mandatory PFI repayments are hidden within that ring-fence. the media seldom reports this as it does not conform to their propaganda about feather-bedded public servants needing to tighten their belts, and raises awkward questions about private sector provision of public services.

Surprisingly the 1997-2008 labour governments privatised more civil service jobs than the Thatcher and Major governments combined. In 2004 labour announced 100,000 job cuts in the civil service leading to increased outsourcing to fill in the gaps that had been left in service delivery:

Initially it was delivered through a massive programme of outsourcing government department’s facilities, IT and security functions, through which staff were TUPE transferred to private firms. Much of this went on under the radar, usually only registering with the media when, for example, a national institution like the British Museum had so few security guards that it had to close important galleries to visitors.

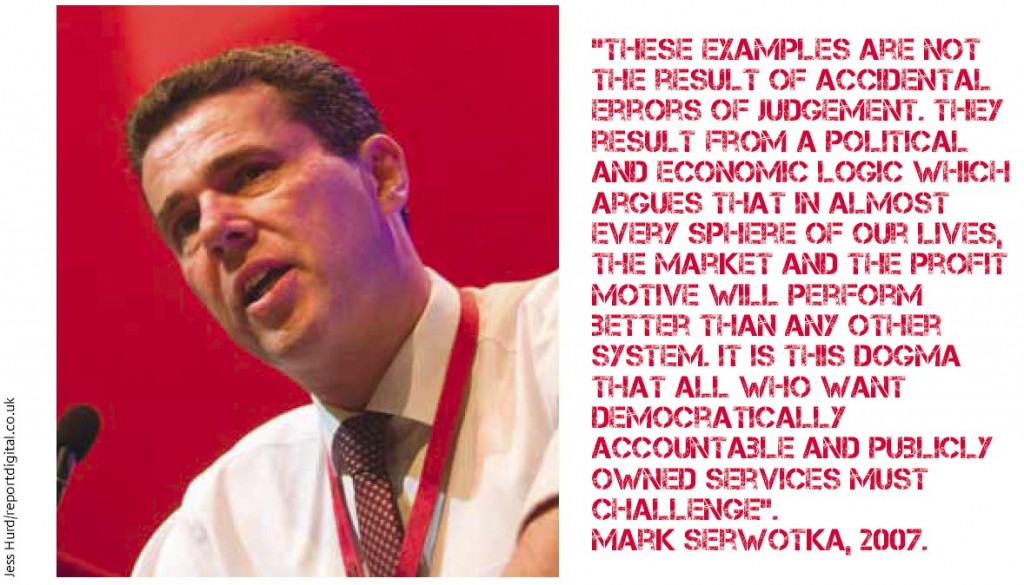

The privatisation of the Ministry of Defence’s Defence Evaluation and Research Agency (DERA) is perhaps the most glaring example of dubious privatisation. although DERA was performing will, in 2003 the government decided to privatise part of it, and Private-Public partnership called “QinetiQ” was created, after which the 10 senior civil servants responsible for taking the company into the private sector saw their total personal investment of £540,000 transformed into £107 million. Graham Love, the company’s CEO, saw his £110,000 investment turn into £21 million. Mark Serwotka, PCS General Secretary, called this “obscene”, but the UK Minister for Defence Procurement described it as “a model for future privatisations“.

The booklet then moves on to privatisation and the media:

The modern idea of objective reporting is little more than a century old. There was little concern that newspapers were partisan so long as the public was free to choose from a side range of opinions. Newspapers dependent on advertisers for 75% of their revenues, such as the Guardian and Independent, would not have been regarded as independent by previous generations of radicals, trade unionists and socialists. Balance was instead provided by a thriving working class-based press. Early last century, however, the industrialisation of the press, and the associated higher cost of newspaper production, meant that wealthy private industrialist backed by advertisers achieved dominance in the mass media. Unable to compete on price and outreach, the previously flourishing working class press was brushed to the margins.

Finally the booklet moves onto Trade Unions and the media:

Trade Unions and the public sector do not enjoy good media coverage. This makes it much easier to dismiss our arguments against the outsourcing and privatisation of public services.

The media’s subservience to power is demonstrated through the manner in which it selects headline stories, frames the order of discussion, and chooses (or excludes) specific interviewees. Viewers of Sky, CNN and most other channels receive the latest data fro the Stock Markets with their breakfast – the FTSE 100’s statistics will scroll past on ticker tape keeping viewers up to date on industrial accidents, or the daily devastation of the rain forest.

The media’s response to the 2008 financial crash and the credit crunch is a case in point. The very people who caused the disaster – bankers, stock brokers and hedge-fund managers – where wheeled into studios to explain it. Trade Unionist, and those who long predicted that financial deregulation would produce this result, were excluded. this media consensus made it much easier to forge a political consensus whereby, token noises aside, City bankers are left unmolested to reap huge bonuses from taxpayer funded banks whilst ordinary people relying on public services will suffer for many years to come.

As public services come under increasing attack from spending cuts and increased privatisation it is important to challenge the view that privatisation and cuts are the only way forward and to take every opportunity to promote the alternatives.

- The complete booklet can be viewed here.

very good summing up of the current ’state of play’

you may or may not have read this but I can recommend it-

“A Guide for the Perplexed” by E F Schumacher

keep going, it will all be worth it in the end

Thanks JD the book looks very interesting.

the book looks very interesting.

This conflates separate ideas – the idea of trade union activity leading to public services – true, the idea that a civilized existence stems from this – misleading, as a healthy free market is the best recipe for a civilized existence but that is something we don’t have and the idea that profit does not equal people – an assumption not based on the few times, usually in a micro context, when a free market operates.

Incentive depends on a free market but I’d agree – not for the profit of oligarchs. Once free enterprise is crushed by both an unwieldy public sector and the oligarchs, the society crashes, as ours is doing.

So what is your solution?

Sometimes perhaps PFI may not have been a bad idea but our political masters seem to have embraced the idea with far too much gusto, leading to some atrocious deals and lousy value

I am probably a bit biased on PFI which was preceded by PPP because the ones I have encountered have always been more expensive and less effective. But the thing that annoys me even more about them is they are not transparent, open and honest.

Jams has hit the nail on the head, Cherie. It’s not that the idea is bad, just as the idea of free enterprise is not bad in itself. In certain key areas – provision for the genuinely poor and incapable – for example, a lad we had in with us doing menial tasks yesterday – it is an absolute essential. Defence, for example, would be ridiculous in devolved form.

There is also the key factor of the giving of employment and I’m the last one who wishes to see anyone living in penury and/or out of work but where a public sector contracts, a private sector expands and people adapt. Again, no one wishes to see children sent up chimneys or living in unregulated sweatshops and I’ve seen enough of the current crop of bosses to know that his business is his only concern and not the workers in it, especially in small to medium business.

I also see a freed-up stm business sector, without councils greedily making it uneconomic for local businesses as a large employment provider. Ditto NMW – it has kept many out of work but it also guarantees those in work about two thirds of what they need to live.

The problem with public sector workers – and I was one, in customs and excise – is that it creates a mentality where, if too secure, unlike private workers, it cuts the incentive to provide value. They might think they are but using BT as an example, it’s actually very poor indeed.

Another example is the current dispute with two rail companies I had. One is ex-BR and the other a private company. The ex-BR is shocking, monolithic when it shouldn’t be, unresponsive to outside, i.e. customer pressure, whereas Arriva has a private mentality and actually does respond to customers.

That’s the whole problem with public sector – the disconnect between the civil servant and the end user, the fat cat sinecure for the upper echelons, for no added value and the potential for abuse, costing the taxpayer billions.

The whole problem with the private sector is the unconcern of bosses for employees and the tendency to monopoly. On the other hand, monolithic private companies’ employees tend to enjoy better pay and conditions.

In answer to your actual question, Cherie, I don’t know – possibly something in the middle.

Personally I haven’t seen a disconnect between public sector workers and the end user, certainly not from the ones that actually have contact with customer. The higher levels yes, I would agree (and those are the ones with the obscene amounts of money), but that is also reflected in the private sector. When I say private sector I mean the big corporations not small private enterprises which are a different thing entirely.

If you look into the companies that take over public services you begin to see common threads – just a few companies bidding for the work, ex ministers with a vested interest, big money for the shareholders and reduced services. The example of QinetiQ above is one such example.

I was going to use the possible privatisation of water supply as another. Whereby people who couldn’t afford it would be denied the right to water but Janice has commented below with a RL example of that sort of thing in action.

As usual those with all the money hold all the aces.

Privatization in some areas came long ago to our province. I remember when much younger stumbling over a body on the street. Being in the medical world at that time I recognized he was having a Grand Mal seizure. Imagine my shock when the ambulance arrived the medics would neither attend to the man nor take him to the hospital till someone paid for said ambulance. I did pay them of course – $35.00 at that time was a hefty chunk to pay – I quickly saw one example of the down side to privatization…

That is a very good example of what is wrong with privatisation of public services. Every thing may start out rosy, (although I haven’t seen much of that in services that I have seen privatised) but it all turns sour in the end.